How to Implement Service Design In Complex Systems

Chief among the tools she suggests we embrace when designing for complex problems are futures thinking, systems thinking, and psychological change management. She also suggests a greater emphasis on designing the politics of the design brief, upfront stakeholder analysis and engagement to understand collective intelligence, and spending more time at the beginning of the design process on problem-framing and hypothesis formation. Additionally, for service design implementation to succeed, she spoke of a need for a leadership mindset shift where people embrace a mentality of constant improvement and accept failure as part of the iterative nature of the design process.

- Embrace futures thinking, systems thinking, and psychological change management

- Greater focus on designing the politics of the brief (who might be your roadblocks and what do they need to say yes) using collective intelligence tools including stakeholder analysis and engagement to surface and solve for these issues early on

- Upfront hypothesis formation (rather than the normal design process where we wait for the hypothesis to emerge at the end)

- Mindset shift to a mentality of constant improvement and accepting failure as part of the iterative nature of the design process

How Did Agnes Discover Service Design?

Agnes spoke to us from Paris where she has lived since 2018 following a 20 year career in civil service in Singapore. Agnes started off telling us a little bit about how she got into the field of design.

In Singapore, Agnes covered 7 portfolios including defense, labor policy, social welfare and community, and public sector innovation. She fell into design during her public sector innovation work. At the time, she was looking at all the tools available, but none of them really spoke to her. Everything was very efficiency driven. It was all very hard and about KPIs and benchmark score cards. But she felt there was nothing about citizens and nothing about why you do this as a government.

Then Agnes discovered IDEO’s work, which immediately clicked with her. When she was offered a post-grad scholarship, she decided to do a one year work attachment at IDEO instead of doing a traditional MBA or MPA. While at IDEO, she was struck by a question a service designer asked, “This is such a good idea (design)…Why can’t they (a tech company) implement these good ideas?” This question really stuck with Agnes as she continued her work in the public sector.

Now Agnes’ goal is to help clients and people who work in complex systems like government to understand how to implement these good ideas of design. She is doing so through her consultancy, MindTheSystem from Paris where she’s lived since 2018 after 20 years of living and working in Singapore.

Agnes divided her talk into three subsections:

I) Understanding Complexity -“Why can’t they implement this great idea?”

II) Implications for Designers

III) Practices for Navigating Complexity

I) Understanding Complexity

“Why can’t they implement this great idea?”

What Is Complexity and Why Is It Increasing?

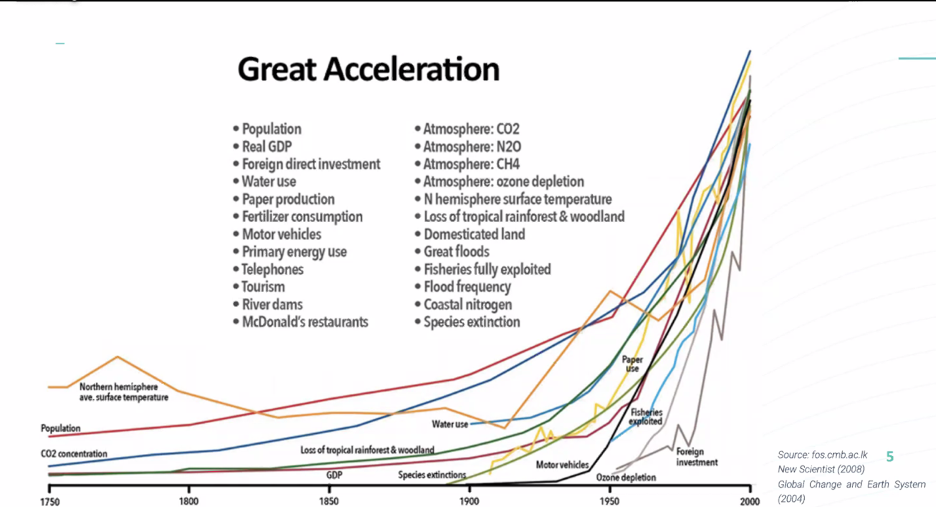

In the first part of her talk, Agnes discussed complexity, demonstrated why it is increasing, and emphasized that this increasing complexity is why now more than ever a toolkit of design can help with the challenges we face today.

She spoke of how we are in a period of unprecedented acceleration of many different systems. Everything from atmospheric CO2 to population growth to species extinction is increasing exponentially. This is compounding the levels of urgency of many competing needs and the complexity of systems as these accelerations play off of each other.

In government and other complex systems, there are multiple competing interests and multiple metrics that might be used to measure success. She gave the example of a government in charge of overseeing development where they are simultaneously responsible for reducing the causes of climate change but also with encouraging economic expansion.

In a complex system, government is charged with considering the interests of multiple parties. When there is more than one bottom line, the success of one metric can come at the expense of another.

Deciding what can be considered success in a complex system with multiple bottom lines can be…complicated.

Agnes pointed out that the trend of the great acceleration is only going to get steeper in the coming years of the 21st century. We have a gathering storm of climate change, technological disruption, and demographic shifts, among other major accelerations.

Factoring these major accelerations into our decisions makes the need to know how to design for complex systems ever more urgent.

Donald Rumseld famously spoke of the known unknowns — things we know we don’t know — and unknown unknowns — things we don’t know we don’t know.

As complexity increases and the great acceleration compounds, it becomes more obvious that we have unknown unknowns. So how do we plan in this environment?

What Does a Wicked Complex Problem Look Like?

To demonstrate what a complex, wicked problem might look like, Agnes gave us two examples from her work in the Singapore Government.

Example 1:

In the first instance, she told the story of a flooding problem in Singapore. For decades, Singapore worked on expanding the capacity and maintenance of their drainage system. Consequently, there was no flooding for 2 decades. Then in 2010, they experienced massive floods. At first glance, it looked simply like a drain capacity problem. However, in actuality it was an issue of rising sea levels and climate change.Agnes pointed out that while the immediate cause of flooding is heavier downpours and a drain capacity that cannot keep up, as one looks deeper, in a complex problem, the nature of the problem will evolve and start to involve many agencies such as urban planners and those who deal with climate change. Now Singapore knows that to deal with flooding — they need to invest over 100 Billion Singapore dollars over the next 50–100 years to shore up their coastal defenses.

This example that shows how a simple presenting problem can morph to be something completely different and it brings up the question:

As a designer, how are you going to understand the true nature of the presenting problem and thus the solution?

“A designer is a problem solver.”

Example 2:

As a second example, Agnes spoke about the policies of the Singapore government around massive population growth, which used to be a primary concern. In the 1970’s and 1980’s the Signapore government had a “stop at 2” policy that provided incentives for parents to stop at having 2 children. However, fertility rates dropped drastically to 1.24, which is well below the replacement levels of 2.1. Consequently, the government had to switch its position and now the government is trying to incentivize the people of Singapore to have more children with policies like giving baby bonuses. However, despite efforts, nothing has succeeded in bringing fertility rates back up. This example brings up the question:As a designer, how are you going to be able to predict the long-term impact of your policy changes?

What Are the Characteristics of Complex Problems and What are Their Implications?

Next Agnes outlined the characteristics of complex problems and shared with us the implications for service designers:

- Complex problems are multi-dimensional and no one individual can see the whole system.

>>The implication is that there are different perspectives to uncover and different goals to navigate. It can be hard to agree on outcomes. - In complex systems, trends can change suddenly.

>>The implication is that past data may not predict what comes next. - Complex problems are subject to the butterfly effect. A small change in conditions can have a significant long-term impact.

>>The Implication is that what works in one context may not work in another. - In complex systems, it is impossible to predict people’s behavior.

>>The implication is that “feedback” in the system can cancel out what you do.

Example:

As an example of how impossible it is to predict people’s behavior and how the feedback in the system can cancel out policy goals, Agnes offered up a true story popularized among practitioners of systems thinking called the Cobra story. In the 1940’s, the British government tried to constrain the Cobra population. The government paid for each cobra that was caught and brought to them.However, the result was the cobra population started going up. Why? People bred cobras to get the financial incentives!

The government realized what was occurring, so they stopped the incentive program. But what happened next? People had no reason to keep the cobras and released them into the wild — the population went up even more!

This is an example of the feedback in the system cancelling out the initial policy of the government.

To Solve Complex Problems, Linear Reasoning Won’t Apply. You Need Ecosystem Reasoning.

Agnes shared with us that to solve complex problems, linear reasoning will not apply. Instead, when operating within a complex system, ecosystem reasoning is necessary.

Agnes pointed out that ecosystem reasoning is not only necessary in the public sector, but in the private sector also because complexity is getting prevalent in the business world as well.

What is a business ecosystem? Amazon is an ecosystem. Facebook is an ecosystem. One study by McKinsey suggests that just 12 ecosystems will account for 30% of global revenues by 2025 representing $60 trillion in revenues.

To better understand ecosystem reasoning, Agnes recommends reading the e-book, Ecosystems Inc., Understanding, Harnessing and Developing Organisational Ecosystems.

Example:

Agnes spoke about Singapore’s Emerging Stronger Task Force program and how design thinking helped certain task forces to be successful.The government created 7 task forces focused on things like smart commerce, environment, sustainability, and supply chain digitalization. What was interesting about it was it was supported by design companies doing design sprints. And what that did was bring together companies who never worked together before. They were asking questions like how do we turn the current crisis into opportunities?

What determined whether the task forces succeeded was whether designers were able to navigate the complex space of having multiple stakeholders rather than a single client.

II) IMPLICATIONS FOR DESIGNERS

So How Do You Determine If You Are Operating in a Complex Space?

Agnes presented ideas from Rob Ricigliano of The Omidyar Group about how to recognize if you are operating in a complex space:

Nature of the Problem:

1) Ground-hog Day syndrome: problem keeps cropping up again and again

2) Whack-a-Mole: solve the problem, another comes up that is linked to the first problem you are trying to solve

3) Actions make things worse

4) Problems keep morphing: think you understand problem, then it keeps changing

Nature of Goals:

1) Hard to find agreement on what is a good outcome

2) Diverse stakeholders with diverse needs/motivations

Nature of Environment:

1) You are overwhelmed by pace of change

2) Solutions that worked in one context don’t work in yours

Source: Rob Ricigliano, Systems Practice, The Omidyar Group. Free course by Acumen Academy, https://plusacumen.novoed.com/#!/courses/systems-practice-2021-2/home

Identifying Complex Problems: Important but Murky, Clear but Questionable

Agnes also gave us a second way to recognize if you are operating in a complex space with her own framework where she bucketed complex problems into 2 archetypes for us:

- Important but Murky

- Clear but Questionable

In Agnes’ framework, Important by Murky problems usually have ambitious goals with inspiring but vague visions. For example, anything dealing with digital transformation or cultural transformation tends to be an important but murky problem. Important but murky problems also have a diverse group of stakeholders with different opinions who often will define the same term in a variety of ways. This can make it challenging to agree on what outcomes the group wants. Additionally, with important but murky problems, the understanding of the problem also keeps morphing.

“I ask 10 different people what is ‘Digital’ and I get 10 different answers.”

Clear but Questionable problems are usually clearly scoped with a pre-supposed solution. Often you are treating the symptoms of a larger problem and in many cases, you find yourself in a situation where your “Boss said we just had to do it.” People will often be basing their decisions off of the idea that, “We’ve tried something like that before.”

Example:

As an example of Clear but Questionable complex problem, Agnes gave the example of the period immediately following the 9–11 terrorist attack where many governments were building bulwarks around critical infrastructure as the primary means to prevent terrorist attacks. However, we had to be cognisant that critical infrastructure defence was only one of the solutions required in a basket of solutions. Combating terrorism required intelligence and real-time sharing of information among countries. The solution to the problem is not one magic bullet.

So, When You Have Identified That You Are Operating In A Complex Space, What Do You Do About It As A Designer?

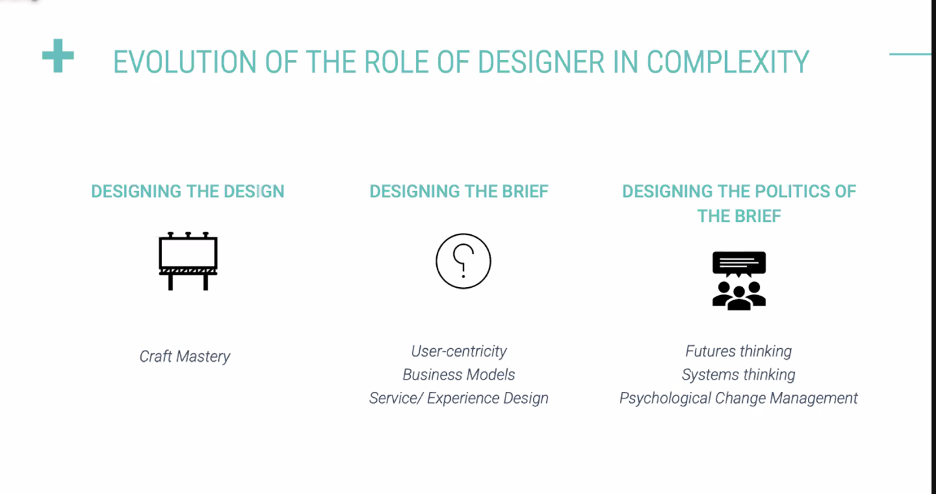

Agnes sees the role of the designer evolving in the space of complexity. She suggests the role of the designer is threefold, to:

- Design the design

- Design the brief

- Design the politics of the brief

Designing the Politics of the Brief is Becoming More Critical

When operating in a space of complexity, the role of the designer is evolving and change is needed in how we design the politics of the brief, particularly when attacking things like climate change, poverty, social equity, and sustainability, which are highly complex.

To better design the politics of the brief in the space of complexity, add in tools including:

1. Futures thinking

2. Systems thinking

3. Psychological change management.

III) PRACTICES FOR NAVIGATING COMPLEXITY

The P.A.V.E. Model

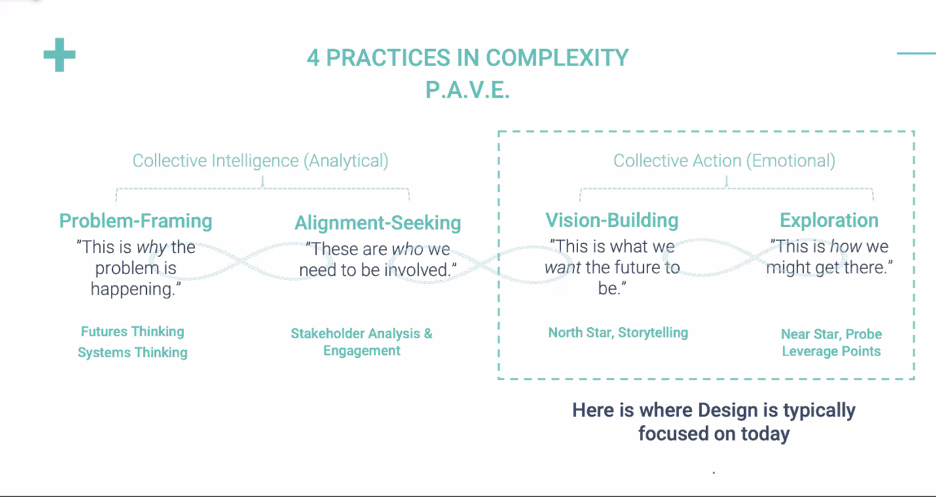

As one method for navigating complexity, Agnes presented the P.A.V.E model which consists of 4 practices and emphasized that they are non-linear and iterative.

The 4 practices of P.A.V.E. are:

P — Problem-Framing

A — Alignment-Seeking

V — Vision Building

E — Exploration

Problem-Framing:

Describes why a problem is happening and what the problem looks like, not only today, but what will it look at least 5 or 10 years out so you can design toward that future and towards those future drivers.

Alignment-Seeking:

Consists of stakeholder analysis and engagement. “If we are going to solve this problem, who do we need to involve upfront?”

Vision-Building:

Includes storytelling and finding the North Star, which people envision what they want the future to be.

Exploration:

Discusses the ways of “how we might get there.” It is not just finding one silver bullet, but finding a portfolio of solutions and requires probing all the different leverage points in the system.

Agnes added that when designing for complexity, she believes there are 2 things to aim for: 1) designing for Collective Intelligence and 2) designing for Collective Action.

In her P.A.V.E. model, Agnes buckets Problem-Framing and Alignment-Seeking under Collective Intelligence and Vision-Building and Exploration under Collective Action.

Agnes suggests that Collective Action, which includes Vision-Building and Exploration, is where design is typically focused on today. Agnes thinks that service designers are currently really great at designing for collective action by bringing people together with tools like brainstorming and facilitation and then making future visions tangible very quickly with tools like prototyping and wireframing.

However, Agnes suggests that to deal with complex problems, designers need to invest more time in the collective intelligence space. This includes Problem-Framing using tools like systems thinking and futures thinking and also Alignment-Seeking using tools like stakeholder analysis and engagement.

So How Do We as Service Designers Spend More Time in the Collective Intelligence Space? How Do We Set Up Problem-Framing and Alignment? Some Questions To Ask Ourselves/Our Clients:

IMPORTANT BUT MURKY PROBLEMS

If you find yourself in the space of an important but murky problem, ask yourself/your client:

* Why should anybody care?

* Which stakeholders should you focus on first?

* What are their pain points and motivations?

* Can you think of three key areas where you might start?

Agnes told us this approach to important but murky problems, “completely flips the whole design equation around because for the first time, we are not starting with the end-user, we are really starting with our universe of stakeholders that form the system in which we need to implement solutions, and a portfolio of solutions to tackle a complex problem.”

CLEAR BUT QUESTIONABLE PROBLEMS

If you find yourself in the space of a clear but questionable problem, ask yourself/your clients:

* To step back and see what other factors are connected to the problem. They might not be within your organization/team.

* If this is no longer a problem, what would it look like?

* Who else needs to know/be persuaded about your assessment? What do they need?This line of questioning helps participants see the larger systems at play and problem framing will shift naturally.

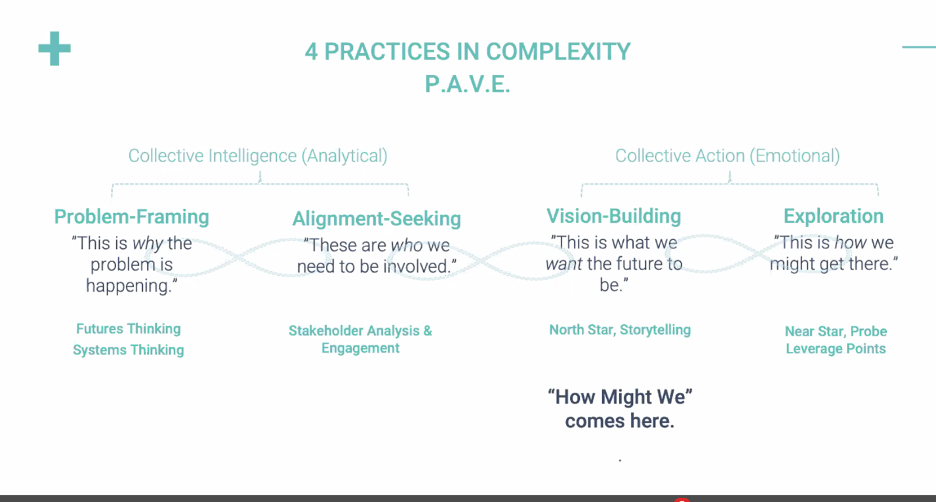

Where Does the, “How Might We,” That Service Designers Learn to Use Fit Into the P.A.V.E. Framework?

Some service designers may wonder where the “how might we” that service designers learn to use fits within the P.A.V.E. framework.

“How might we” goes in the V of P.A.V.E., during Vision-Building.

Doing Stakeholder Analysis Before the User Research

Agnes gave an example from her work in the Singapore government when they were designing for population growth and where they put extra emphasis on stakeholder analysis — they did the stakeholder analysis before the user research in the design process.

The way this was implemented was that designers asked themselves what are all the touchpoints for parents with the government through the lifecycle of having a child — from expecting to when the child grows up. Then designers met with the 15 different agencies who were part of those touchpoints and had senior level civil servants from each agency go into people’s homes to ask the questions done during typical user research and ethnography. Agnes shared that practicing stakeholder analysis in this manner showed how all the stakeholders were interconnected and provided designers with many clients, not just one.

A Hypothesis Softly Held

In Agnes’ examaple, they also spent a far longer period on hypothesis-building, asking questions such as:

* How does the challenge present itself?

* What are the possible interventions?

* Who is involved in the system?

Agnes discussed how in her experience, designers are hesitant to enter into the hypothesis building space and she believes that they need to be more bold by creating some form of hypothesis upfront instead of waiting for the hypothesis to emerge at the end of the design process. She talked about how this could be a, “hypothesis softly held,” where there is space for the hypothesis to shift as the design process unfolds.

In Agnes’ example with the Singapore Government, the vision that came out of this process was a desire to provide a seamless touchpoint with government for parents from start to finish in the experience of having and bringing up children. The idea was to create one platform where parents could do all things related to their child including registering the baby’s birth, signing up for baby bonuses, keeping track of vaccination records, and enrolling in public school.

When Operating in a Complex Space, a Shift in Leadership Mindset Is Required

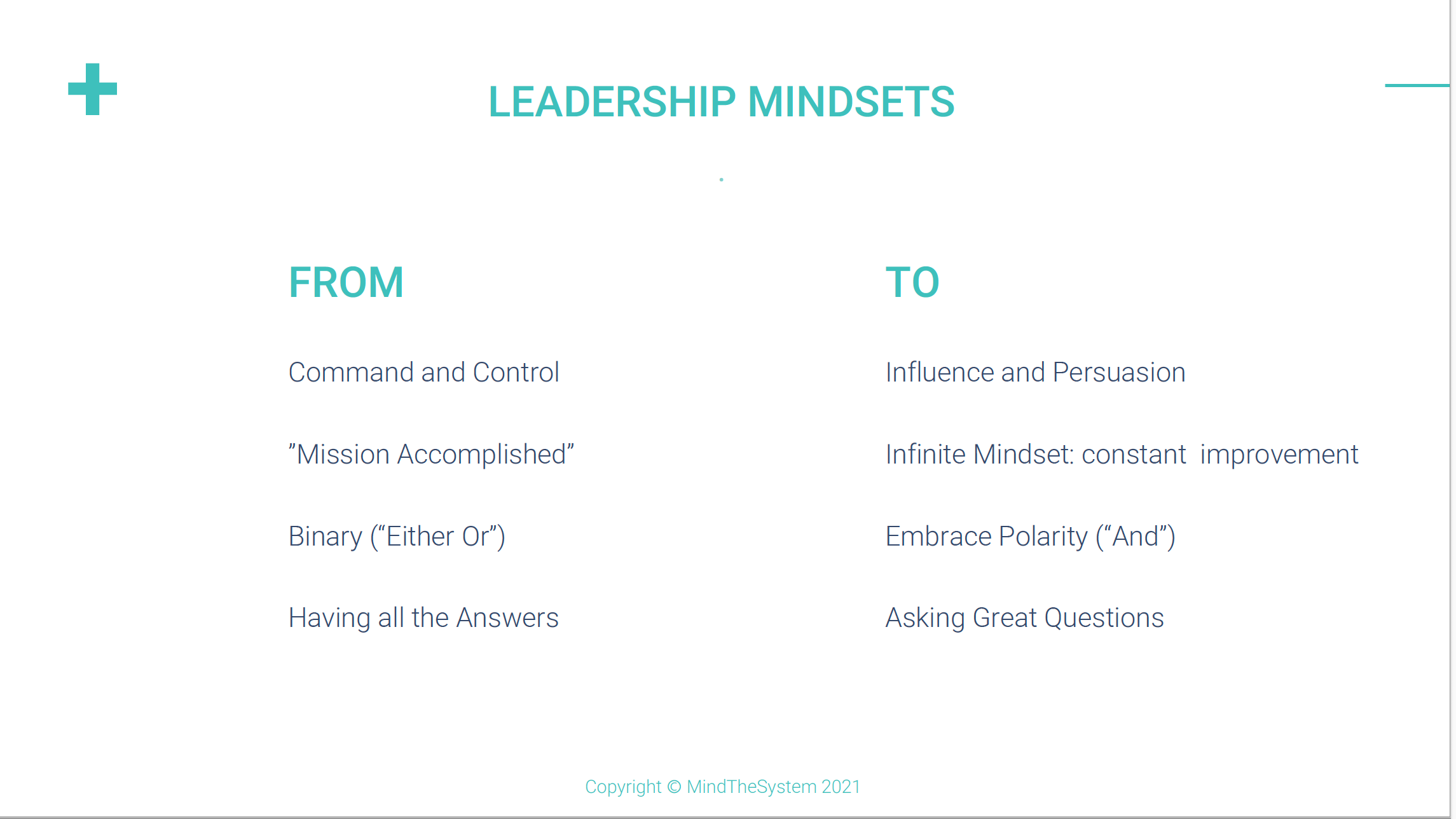

Agnes spoke about several shifts in leadership mindsets that can help navigate complex spaces as seen in the chart below:

So What are the Barriers to Practicing Complexity and Which Do We Have to Watch Out For Most?

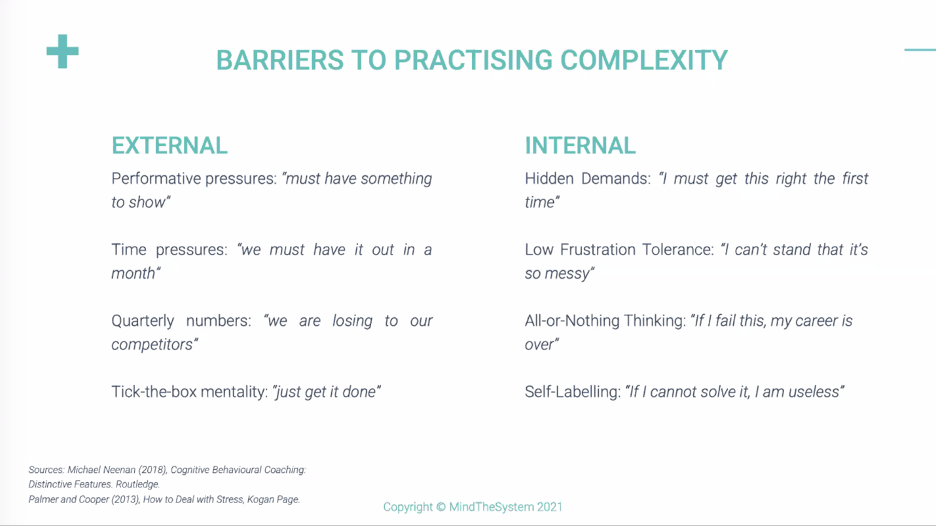

Agnes presented several barriers to practicing complexity. She discussed how while external barriers do exist such as performative measures, time pressure, quarterly numbers, and tick-the-box mentalities, it is the internal barriers related to personal accountability that are more nefarious for designers. Internal barriers include a mentality that we must get it right the first time, worries about how a failure may end your career, and thoughts of how if you cannot solve the problem you will be useless.

Complex Problems Don’t Lend Themselves to Perfectionist Tendencies

Agnes presented 5 ways that maladaptive perfectionism gets in the way of practicing in an environment of complexity and 4 shifts in mentality that can help designers succeed.

When operating in complex systems, key among the shifts that can help designers succeed is to embrace a mentality of constant improvement and to accept failure as part of the iterative nature of the design process.

Question and Answer Session

Favorite Questions to Ask People To Tease Out the Complexity of a Problem:

During the Q&A, Agnes shared with us some of her favorite questions to really get the complexity of a problem out on the table and get people to open up:

- If I see you in the street in 6 months’ time, and you tell me the issue is resolved, what does that look like?

- What are 1 or 2 assumptions that you are making? (People can get stumped. But it surfaces biases they bring to the table)

- If you were talking to your boss, who would they say are the 3 most important people who you need to talk to?

These questions serve to get people out of their own shoes and to go one or two levels higher in their thinking and to see the system as a whole, to open the aperture up a lot wider and see all the connections around them.

Designing the Politics of the Brief Improves Implementation Efficacy

Agnes also reemphasized the importance of designing the politics of the brief. The purpose of designing the politics of the brief is ultimately to improve implementation efficacy. If you start with the question of what are all of the implementation barriers that we are going to face and factor that in, all the way up front, the nature of the question begins to change. Who are the people you need to get on board from the very beginning, and what is important to them so you are able to implement down the line?

“Policy is implementation….You can write the most beautiful policies on paper…but if it doesn’t get implemented, it is nothing.”

Signs of a Team’s Readiness to Practice These Design Tools for Complexity

Agnes was also asked about what signs exist about a team’s readiness to practice some of these design tools that she talks about — are there indications that a team has already done the deep work and mindset shift in their approach to problems that is required.

Agnes responded that you can tell when someone gets it — when they are prepared to question their own assumptions, that’s when participants are ready to practice these tools of design. Agnes also said it is not an issue of organizaitonal structure, but an issue of mindsets and capabilities.

Agnes said we are at a unique time where people are willing to question the way things have been done. People have an appetite now for how design can take them to a different place. But people don’t know where to begin — Where do they even start. And this is where she is getting a lot of inquiries around — How do you build your internal capabilities to start? So she is focused right now on how to help teams step their way through complexity.

Further Resources

During Q&A, Agnes suggested 3 further resources from outside of the field of service design to help understand complexity:

- Cynefin framework, invented by Dave Snowden while he was working in the 1980s for IBM. Way for you to understand or sensemake your problem

- The Omidyar Group, started by the founder of E-Bay, is developing systems design practices that are useful

- The field of systems thinking

After the talk, Agnes also sent along these helpful resources:

Find this content interesting or useful? Follow the SDN New York Chapter on Instagram, LinkedIn, Twitter, and/or Medium to stay connected. Anyone is welcome to join their Meetup group and events. You can also find them on the global Service Design Network website — learn more about the larger SDN community there as well.

Share your thoughts

0 RepliesPlease login to comment