This article is part of Touchpoint Vol. 11 No. 3 - Service Design and Change Management. Discover the full list of articles of this Touchpoint issue to get a sneak peek at more fascinating articles! Touchpoint is available to purchase in print and PDF format.

“We need a new organisation-wide training strategy. We have been training the most critical teams in the organisation in the same way since the 1980s and we need to move out of the dark ages. Problem is, the teams are so used to the way things are done. How can we build the strategy in a way that brings people along as we go?” This was a question one of our clients posed to us when considering how she would redesign training for an entire department of a Fortune 500 company. Inherent in her question are two principles that drive our perspective on change management. Firstly, it is the people – not the initiative at hand – that play a leading role in enacting change. Secondly, change management needs to be baked into the initiative itself and not treated as a separate activity.

We’ve seen executive teams spend months designing a strategy or new initiative in isolation from the organisation, conduct a grand unveiling of the transformation agenda, and then focus on typical change management activities such as socialisation and training. The trouble with this approach is that it separates change management from the initiative itself, assuming that people will come along after the ‘grand reveal’. Even if they do, the energy can be hard to sustain. Perhaps more importantly, this approach misses the opportunity to design user-centered change management activities based on real insights about how employees and stakeholders react to the new initiative. Finally, this approach to change management can disillusion employees who are experiencing change fatigue1 — which is the opposite of inciting stakeholder desire to participate in and lead the change.

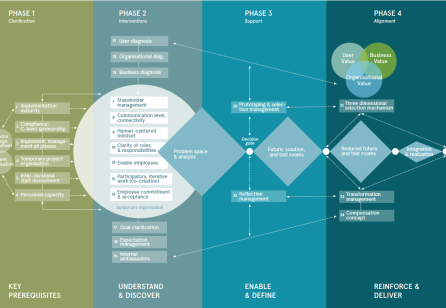

At Bridgeable, our model of organisational transformation finds its roots in Jim Collins’s seminal book, Good to Great, and we argue that in this model, service design is itself a powerful tool for delivering change management, and an antecedent for transforming organisational design and culture, and pursuing new strategies.

The core idea within Good to Great is a ‘flywheel’ model of innovation. An actual flywheel is a mechanical device for storing rotational kinetic energy. Turning a mechanical flywheel is very difficult initially, but with each revolution, it becomes easier and easier, until eventually the flywheel has a self-maintaining momentum that takes an even greater force to stop. Collins argues that this is a metaphor for the transformation model employed by the most successful companies that have made the transition from ‘good’ to ‘great.’ It is also an explicit rejection of ‘big bang’ models of organisational change: “There was no launch event, no tag line, no programmatic feel whatsoever.” Rather, these highly successful organisations achieved dramatic transformations with a consistent set of small steps all building in the same direction2.

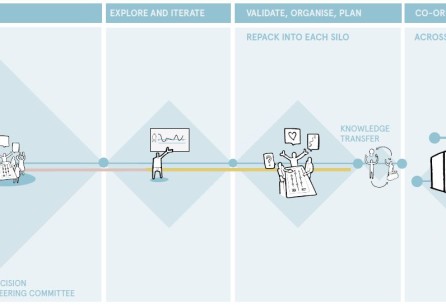

Designers instinctively apply similar principles within the scope of their projects: they build prototypes or minimum viable products, put them in front of endusers, learn and iterate at increasing levels of fidelity, and repeat. The flywheel model is a conceptual framing that extends our natural mode of prototyping from a service or experience towards a broader organisational transformation, where the change management isn’t a distinct workstream or programme, but is integral to the approach itself. As Collins observes, “Under the right conditions, the problems of commitment, alignment, motivation, and change just melt away. They largely take care of themselves.”3

Let’s look at how we have seen this work in practice. By far the most common kind of transformation we work on is an organisational transformation towards customer experience or customer-centricity. For firms with a desire to make their organisation and offerings more customer-centric, service design and humancentred design are a natural fit. There is often a desire to start top-down, with a grand strategy that maps out how to achieve that goal, and a certain amount of up-front work to align on a ‘north-star’ vision is important. But we always recommend that process is relatively brief, and importantly shouldn’t end with an extravagant presentation of the strategy across the organisation. Instead, once the direction is clear, we believe an organisation should quickly move on to solving a practical service design problem within the business.

For one Fortune 500 client, we worked with their newly-formed customer centre of excellence to complete a brief engagement developing a customer experience strategy, and then turned our attention to redesigning a single (but thorny) customer touchpoint. That project was classic service design: understand the customer journey and organisational context, co-create prototypes of new touchpoints with both internal stakeholders and customers, iterate and refine those prototypes to validate design decisions with new customers and internal players, integrate with the broader ecosystem and bring it to market, and finally measure the results. Change management was never a line item on the project plan, but it was actively at play nonetheless.

Key internal stakeholders were active participants in co-creation and ongoing prototype validation. Through their participation in the design process, those stakeholders became dedicated advocates and champions for change. They couldn’t wait to tell their managers and co-workers about the great project they had done and the great results it had produced. People in other areas of the business heard about that success and beat a path to the door of the centre of excellence. Could we take a customer experience approach to their problem too?

Share your thoughts

0 RepliesPlease login to comment