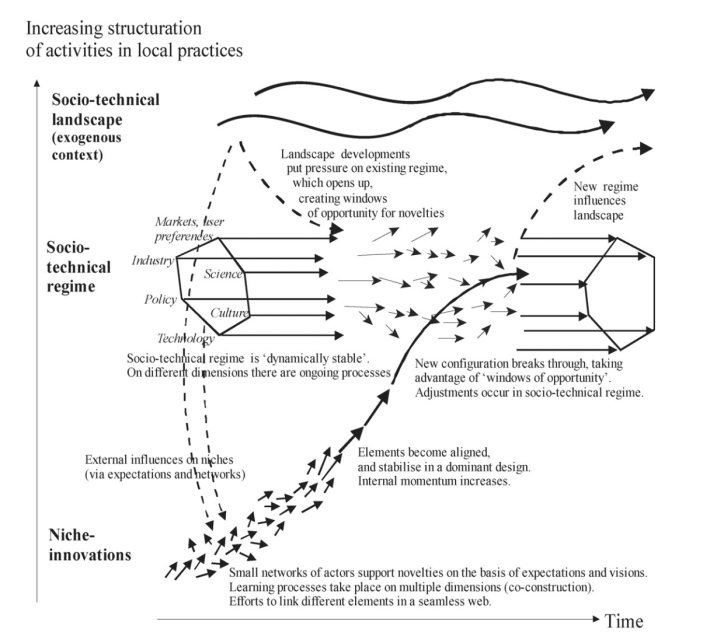

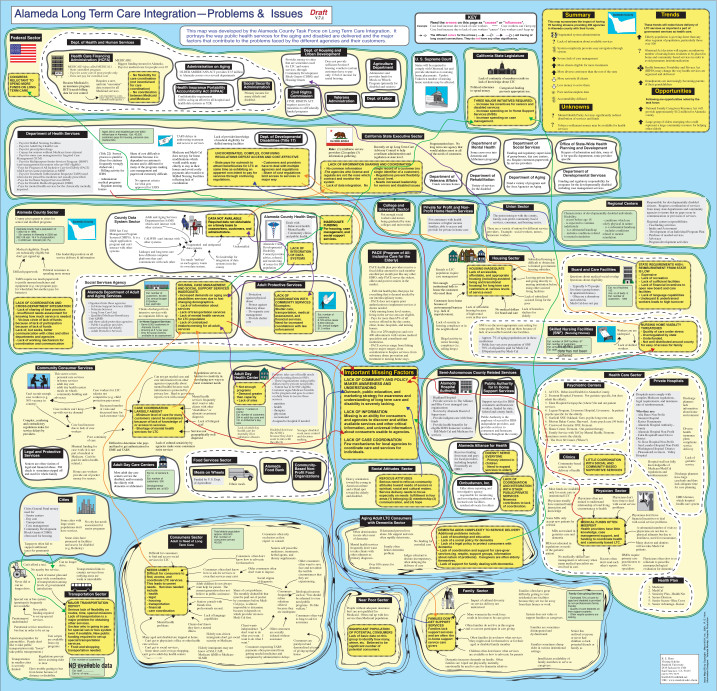

In the macro level of the Geels´ MLP framework (see also Figure 2), current and future trends are important as they drive the changes such as megatrends, pandemics or crises. These landscapes, influencing meso- and micro-levels, can be ‘gigamapped’ via desktop research or mapping workshops with experts and users on the ground. Mess Mapping can also be useful as it can map out the wicked problem or the ‘mess’ that is at hand in a collaborative manner (Horn & Weber, 2007).8

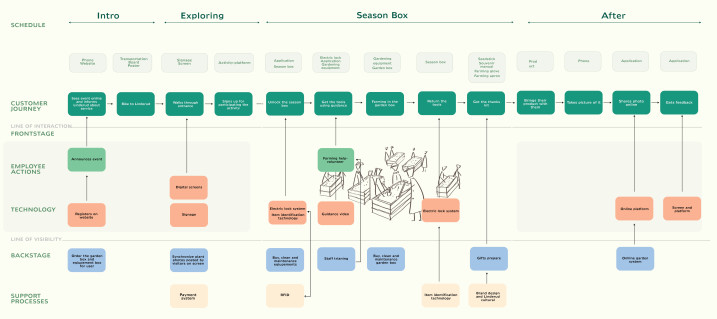

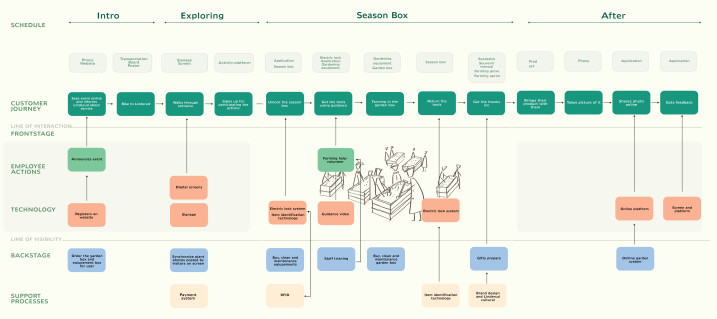

To create change in the meso- and micro-levels, we propose using service blueprints to create a diagnosis of the supply chain management. These can focus on users, stakeholders or even objects such as shipping containers. Users can be understood as the people who are forwarding shipping containers in a service system. After knowing what is happening in the current service, it is then possible to create the intervention or transition to change it.

A key feature of systemic service design is the recognition that landscape changes such as global warming are triggering systemic change, and wicked problems of macro-level mapping (see above) are fully considered when doing the micro- and meso-level service blueprints.

When designing a service, one should consider all three layers and especially the influence of the macro level. Larger scale transitions also typically require longer timeframes to complete, from ten to 50 years.

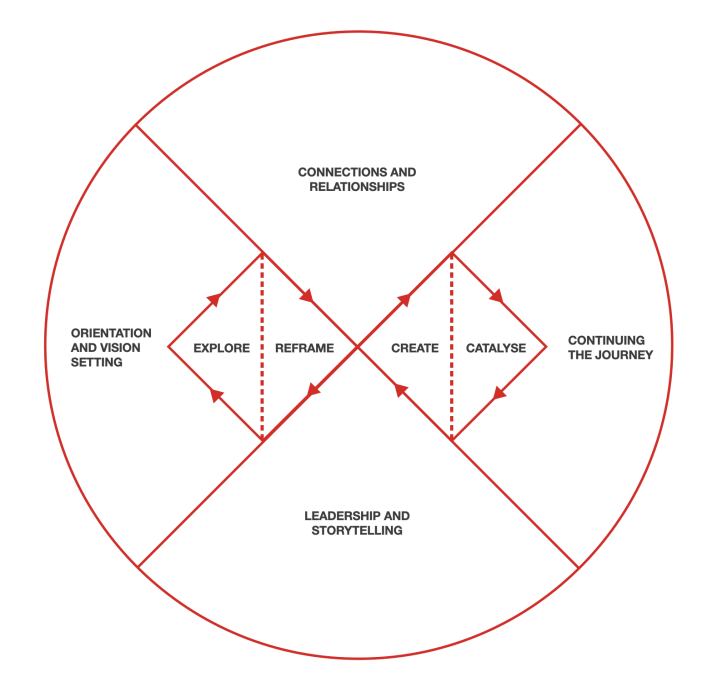

Service design, as an approach, has the aim to connect a web of different people and planetary actors together, making them an active part of a multi-stakeholder participatory design process. In supply chain management, typical stakeholders include material suppliers, producers, distributors, retailers and consumers. As the participants of the process are most knowledgeable on the field they represent, often they can provide most plausible ‘solutions’ or interventions that can create change.

The template itself can be used as a boundary object to facilitate the visualisation of the complexity, but at the same time it can also act as a strategic tool to create interventions. A boundary object is any object (e.g., artefacts, classifications, maps, materialised representations) that handles and organises information and can help in the communication of the information between different parties.

An important aspect of the template is its ability to make complex challenges both tangible and visible. This aids stakeholders to come to a common ground and makes visible the social structures or larger systems that need to be redesigned.

It also allows for the fact that users and stakeholders each experience services from their own perspectives. For example, in a healthcare context, a patient can have a different service experience than both their doctor, and from that of administrative person supporting the service.

Discussing the template

We should not propose a template without critically evaluating it. It is essential to recognise that each wicked, social ‘mess’ is unique and one-of-a-kind (Rittel & Webber, 1973), therefore we cannot make generalisations. Proposing a general template such as that presented in Figure 6 risks oversimplifying a problem, although the Mess and Gigamapping approaches themselves can uniquely describe specific situations.

It is also good to bear in mind that using the template requires adaptation to each specific situation. The template in Figure 6 proposes using Mess/Gigamapping, service blueprints and the MLP model together in a systemic service design approach and facilitation, and other tools could still be added-on if needed.

Setting up boundaries on what to map, and what not to map, within the template is an important aspect and will always somewhat limit the use of the template. One will always need to prioritise what is important in a service system to be able to design it.

It is still important that when designing an intervention in a system, one needs to be aware of the unintended consequences that might affect other areas. These could be positive or negative, which highlights the importance of having the right people at the table to discuss the problem at hand. The template helps guard against reductionist thinking and to recognise that there are no right solutions, but rather ones that will be ‘muddled through’ (Sevaldson, 2022).7

By using service blueprints, it is possible to map the experience of multiple users and stakeholders in a system. At the same time, by applying systems design, one can understand how a change in the system can make the experience of e.g. an employee better, so that they are motivated to drive change in a participatory manner.

Our template, based on systemic service design principles, could be one way to inject agency to the Geels (2005) 1 MPL model. However, this study is limited since the template itself has not yet been tested in practice. Case studies from practice would be needed to determine its value and how it could be applied in the supply chain field, or other fields that require transitions. These could include healthcare, education, tourism and public services in general.

The template could also be further developed to cover explicitly future-oriented or speculative designs through service blueprints, such as Resolution Mapping or Backcasting. Resolution maps and Backcasting share similar principles, where an ideal future is imagined or created by the participants, and then participants look at the necessary steps to achieve it, and potential hindrances.

Conclusions

Through this article, we argue for service design with a systemic angle as a way to facilitate sustainable transitions of complex supply chain systems. We provide a template that can serve as a basis for sense-creation and then, through interventions, shape transitions.

Service design can play a pivotal role in engaging supply chain stakeholders to understand and comply with regulations related to sustainability, but also in the development of new regulations that promote sustainable practices on a macro level. By acting as impartial systemic facilitators, service designers have the potential to overcome the strong dependencies that exist within supply chains, typically caused by the dominant role of buying power effecting the multi-stakeholder collaboration.

We recognise that in contemporary supply chains, systemic service design in collaboration with intermediaries is key in facilitating the sustainability transition and combining micro-, meso- and macro-levels.

Share your thoughts

0 RepliesPlease login to comment